This year, I am going to be launching a new series of blog posts on Pawsitively Intrepid. The “Living an Active Life with a Reactive Dog” blog series will focus on ways to safely enjoy the outdoors with a dog that struggles with reactivity.

This is a topic near and dear to my heart, as my own dog, Glia, is a reactive dog. Glia inspired my love for hiking before her reactivity fully developed, so when she began to demonstrate reactive behaviors, I knew we couldn’t just stop our active life.

It has been a long journey filled with mistakes, frustration, and even sadness that there are some activities Glia will never be able to participate in. However, there have also been goals accomplished, joy, and amazing companionship. And now, about 6 years after identifying Glia as a reactive dog, we have a reliable system in place to still get out and enjoy the great outdoors. Glia has even successfully traveled to over 40 national parks.

There are so many topics to be covered within this blog series. Everything from choosing sturdy, escape-proof hiking gear to teaching your dog how to calm down and safely pass other dogs and people on the trail falls into this blog series.

For those without a reactive dog, I hope that some of these articles can simply give you a better understanding of how to help respect and give space to dog and owner pairs who look like they are working hard on the trail. For those with reactive dogs, I hope this blog series can empower you to become your dog’s best advocate and offer resources that enable you to share many adventures with your dog in a safe and enjoyable manner.

What is the definition of a reactive dog?

Every dog reacts to stimuli around them every day. A reactive dog is simply a dog who “overreacts” to normal stimulus.

For example, a “normal” reaction for a dog when seeing an approaching hiker would be to look at the hiker, possibly give a friendly tail wag, and then be able to refocus on the dog’s own handler when asked to do so.

An example of a reactive dog is a dog who sees an approaching hiker, looks at the stranger and then is unable to stop staring. As the hiker gets closer, the dog’s hard stare may turn into barking, growling, lunging or other “reactive” behavior.

Barking and growling would be an appropriate and “normal” reaction if the hiker were attempting to hit or hurt the dog, but it is an over-reaction to a hiker who is simply walking by on the opposite side of the trail.

To put this a slightly different way, the WholeDogJournal.com has an excellent article by Pat Miller, that describes reactivity as follows:

“Reactive” is a term gaining popularity in dog training circles – but what is it, exactly? In her book Clinical Behavioral Medicine for Small Animals, Applied Animal Behaviorist Karen Overall, M.A., V.M.D., Ph.D., uses the term to describe animals who respond to normal stimuli with an abnormal (higher-than-normal) level of intensity. The behaviors she uses to ascertain reactivity (or arousal) are:

• Alertness (hypervigilence)

• Restlessness (motor activity)

• Vocalization (whining, barking, howling)

• Systemic effects (vomiting, urination, defecation)

• Displacement or stereotypic behaviors (spinning, tail- or shadow-chasing)

• Changes in content or quantity of solicitous behaviorsThe key to Dr. Overall’s definition is the word “abnormal.” Lots of dogs get excited when their owners come home, when they see other dogs, when a cat walks by the window, when someone knocks at the door, and so on. The reactive dog doesn’t just get excited; he spins out of control to a degree that can harm himself or others around him. In his maniacal response to the stimulus that has set him off, he is oblivious to anyone’s efforts to intercede. He goes nuclear.

https://www.whole-dog-journal.com/behavior/causes-of-reactive-dog-behavior-and-how-to-train-accordingly/

Why are some dogs reactive?

While frustration, overstimulation, and other strong emotions can all result in reactivity, for many dogs, reactivity is based in anxiety and fear. These dogs are afraid of the dog or person coming towards them, so they are barking, lunging and growling to tell that stranger to go away. Essentially, these dogs take an offensive approach by reacting early to things, people, or other dogs that make them nervous.

Because so many reactive behaviors stem from fear and anxiety, it is important for reactive dog owners to learn the more subtle body language of our dogs.

For example, in my experience, it has not been common knowledge that licking lips and yawning can be subtle signs of anxiety. The image below, created by Dr. Sophia Yin, gives a few great examples of the body language of fear and anxiety in dogs.

Another common misconception is that a dog that is wagging his or her tail is friendly. The truth is that tail wagging is a major source of communication between dogs. And a wagging tail can mean several different things.

The height at which a dog holds his tail, the speed with which he wags it, and even the direction of the wag is significant.

A dog that is friendly and happy tends to hold his tail in a neutral or slightly raised position. The friendly dog then wags his tail broadly and freely, possibly even with a wiggle of the hips. His tail will likely wag more to the right than the left (as the right brain controls the left side of the tail and is associated with positive feelings).

An agitated dog will hold his tail up and raised. If he is insecure, his tail may wag very subtly and may freeze as he becomes more nervous. With more aggressive intent, a dog will wag his tail very fast while holding it up. These anxious dogs will likely wag the tail more to the left (as the right half of the brain is associated with negative feelings like fear).

So watch your dog’s tail. If your dog has a slow tail wag with the tail at half-mast, your dog may be insecure. And when your dog starts giving tiny, high-speed almost tail vibrating wags, your dog is getting ready to do something. Either fight or flight.

Interested in reading more about what a wagging tail means? Check out this article in Psychology Today or VCA Hospital’s overview of tail language in dogs.

Here is a video example, as the best way to learn tail language is to see tails in action. The following video is from Animal Planet’s Youtube Channel. Watch until around 4:30. At that time the video transitions to zebras.

What is the difference between a reactive dog and an aggressive dog?

For the purposes of this definition, let’s agree to assume that all dogs can exhibit aggressive behaviors when adequately provoked. However, when we refer to an “aggressive dog” we are really talking about a dog exhibiting aggressive behavior without appropriate cause.

At the risk of oversimplifying, aggression is really just a type of reactivity. Just like all squares are rectangles, but not all rectangles are squares. Aggressive dogs are all reactive, as inappropriate aggression is an over-reaction to a normal stimulus. However, not all reactive dogs are aggressive.

Current veterinary behaviorists have done away with the dominance theory and now believe that aggression stems from fear and anxiety. Since fear/anxiety is also the most common cause of reactivity in dogs, it becomes easier to see how reactivity and aggression are linked.

Fear can cause a fight or flight response, so if fear and anxiety are left untreated and continue to worsen, many reactive dogs can turn into aggressive dogs as their fight response intensifies.

To help demonstrate this point, take a look at the Ladder of Aggression created by Kendal Shephard, author of The Canine Commandments.

As you can see in the ladder above, if your dog is reactive due to fear/anxiety, by the time they are staring, growling, and snapping, they are already nearing the top of the aggression ladder.

An aggressive dog is essentially a reactive dog that is skipping steps of the ladder. When anxious and aroused, an aggressive dog might skip straight to snapping and biting rather than walking away or even stiffening and growling first.

The following quote from a VCA Hospital article about fear vs. aggression helps further clarify how aggression can develop from fear.

Fear or anxiety related aggression is perhaps the most common form of aggression in dogs. In reality most types of aggression… likely have a fear or anxiety component. Fear- or anxiety-related aggression may be confusing as the dog might display defensive or offensive body language.

Early manifestations of fear related aggression are typically defensive, displayed to increase the distance between the perceived threat, or communicate ‘stay away’, yet aggression may become more offensive through learning. Aggression is offensive when displayed while closing the distance to the perceived threat. However, even though the displays of offensive or defensive aggression look different, fear and making the stimulus go away are still the primary motivation for the behavior.

https://vcahospitals.com/know-your-pet/fear-vs-aggression

Genetics and previous experiences can play a roll in whether or not your dog goes on the “offensive” or attempts to retreat from something that makes them anxious.

Some breeds of dogs have been selected to guard livestock or alert to territorial threats. Other dog breeds have been selected to display predatory behavior. But even dogs without a genetic predisposition to aggression may have learned from previous experience that aggression was a successful way to avoid or prevent an unpleasant outcome.

An aggressive dog becomes an increasingly dangerous dog when they learn to escalate aggressive behavior quickly. Aggressive dogs are not all a lost cause, as proper management and behavior modification can make a big difference. But it is important that safety is the number one concern when working with an aggressive dog. Safety for you, safety for other people and dogs, and safety for your aggressive dog.

Consider this dog bite scale, originally created by Dr. Ian Dunbar, and adapted into a visual chart by Dr. Sophia Yin.

The best outcomes occur when dogs are in level one and two bite stages. These are the best stages on this chart to get professional help to develop a behavior modification program for your dog. It is much easier to prevent escalating bites than it is to help your dog un-learn a behavior it has already practiced. Dr. Sophia Yin discusses this concept further in her post titled “Was it just a litte bite or more? Evaluating bite levels in dogs.”

Of course, it is even better to address the anxiety before your dog snaps at someone or another dog and ends up on the bite chart at all. If you notice fear and anxiety-related behavior in your dog, don’t hesitate to consult with your veterinarian before problems truly arise.

Veterinary Behaviorists

When choosing professional help in dealing with a reactive/aggressive dog, oftentimes the best resource is a veterinary behaviorist. A board-certified veterinary behaviorist is a veterinarian who has completed additional training studying animal behavior after the standard 4 years of veterinary school.

These board-certified veterinary behaviorists have completed the equivalent of an internship, behavior residency, authored a scientific paper, written peer-reviewed case reports, and completed a comprehensive 2-day test on animal behavior. Essentially, these veterinarians have dedicated their entire careers to behavior. They are amazing resources as they can help with developing management systems, behavior modification programs, and even prescribe anti-anxiety medication when needed.

If you live in the Twin Cities area of Minnesota, Veterinary Behavior Specialties of Minnesota has two board-certified veterinary behaviorists ready to help you and your dog.

How to Live an Active Life with a Reactive Dog

Staying active with a reactive dog comes down to finding success in two main categories: management and behavior modification.

There is so much information to cover about both of these topics. However, since this article is just about the basics, the below information is simply a quick overview. More detailed information will follow in subsequent blog posts.

Management

Management refers to how you manage your dog’s reactivity without attempting to change the behavior. In this category, you need to identify your dog’s triggers and learn how to avoid them. You also need to develop a plan to keep your dog safe when you can’t avoid triggers.

For example, Glia has a couple of triggers.

She is the most reactive towards energetic young dogs, specifically, labrador sized dogs. Any dog who barks or stares at her is extra triggering. Glia can mostly ignore a calm dog who is not engaging with her. Her reaction to triggering dogs typically starts with a hard stare and proceeds to barking and lunging.

Glia also has a high prey drive, so she has a frustration bark when she is on a leash and can not chase squirrels, rabbits, deer, etc.

Now that I know what Glia’s triggers are, I can avoid them. On a hiking trail, this can mean one of three things for us.

- An emergency U-turn (works well for her prey drive and for oncoming energetic dogs). More information about the emergency U-turn can be found at DrSophiaYin.com.

- Creating space by stepping off of the trail. The distance needed for Glia to be able to sit and calmly take treats while another dog walks past is different depending upon what type of dog is walking past. I walk further away from dogs pulling on leash towards Glia than from dogs walking past who are not paying much attention to us.

- Picking Glia up. I have learned that when I can’t make space from a trigger by changing directions or stepping off of the trail (such as when an out of control off-leash dog comes running up to us), I can still create a little vertical space by picking Glia up. Now some dogs will jump on me and still stick their faces in Glia’s, but Glia is less reactive when she is in my arms.

Other ways we avoid triggers are to hike during less busy times of the day or the week. For example, we love to hike nearby state parks on Wednesday (my day off) during the week. So often we only see one or two other hikers mid-day on weekdays.

On weekends, we drive further to hiking locations as fewer people tend to drive very far. Hiking on cold days or when it is raining can also be a great option for some peace and quiet on the trails.

But sometimes, trails are going to be busy, so we always hike prepared. Over the years, I have found a few pieces of gear to be essential for hiking with a reactive dog.

One is a secure harness. It is so important for me that Glia can not escape her harness. So Glia hikes in either a Ruffwear Webmaster, a Ruffwear Flagline, or her custom Groundbird Gear harness. All of these are full-body harnesses. The Webmaster is probably the most secure if you really have an escape artist, as the belly strap can be positioned further back on the dog’s stomach/abdomen. On Glia, this means that her deep-chest cannot slip through the belly strap when it is adjusted for the circumference of her waist.

After two episodes of collar malfunctions (one that broke and one that slipped over Glia’s head), we transitioned to martingale collars if a leash is going to be attached to her collar. Martingale collars have a much lower risk of slipping off.

The final piece of necessary equipment is a sturdy leash. It should be under 6 feet in length, but honestly, I prefer 4 feet in a crowded area.

For most of our national park adventures, Glia walked on a 4-foot hands-free leash made by TuffMutt. This waist leash was secure, as there is no chance of dropping a waist-worn leash. It also kept my hands free to reward good behavior with treats during our exploration of the parks.

On quiet trails, I will often use a longer leash to allow Glia more freedom, but just remember, the further your dog is away from you, the longer it will take you to reach her if needed. A good recall is essential before starting to hike on a long leash.

So overall in the management category, avoid your dog’s triggers, have a plan, walk your dog in less busy areas if possible, and make sure you have a secure leash and harness (or leash and collar) combination. These are all ways to prevent your dog from being placed in a situation where they have a chance to practice reactivity and escalate reactivity to aggression.

Oh, and don’t be afraid to tell people your dog needs space. You are your dog’s biggest advocate and although it can be hard to tell people that they can’t pet your dog or that their dog can’t greet your dog, remember that helping your reactive dog stay safe and protected is important.

As I mentioned earlier, the management of a reactive dog is a big topic and more than can be explored in one blog post. We are working hard on expanding our selection of blog posts here, but for now, here are a couple of websites that discuss various aspects of management in regards to reactive dogs.

The first link is a good overview of topics regarding reactive dogs. The second discusses muzzles as a management and safety tool. The third and fourth links discuss trigger stacking and how to avoid a dog’s triggers.

- New Horizons Veterinary Behavior Services

- The Muzzle Up Project

- “Understanding Dog Trigger Stacking” by PetHelpful.com

- “Are You Trigger Stacking Your Dog” by High 5 Canine Coaching

For some dog-human pairs, managing the reactivity will be satisfactory without additional training. And there are definitely those who figure out a way to be active and still avoid triggers. But for most of us who live with a reactive dog, we will also want to work on changing our dog’s response to his or her triggers to allow us to participate in a broader range of activities. This brings us to the second category: behavior modification.

Behavior Modification (Training)

Behavior modification is basically training. This category focuses on changing your dog’s mindset, reducing the emotions that result in your dog’s reactivity and helping your dog react in a more appropriate manner when they are feeling fear or anxiety.

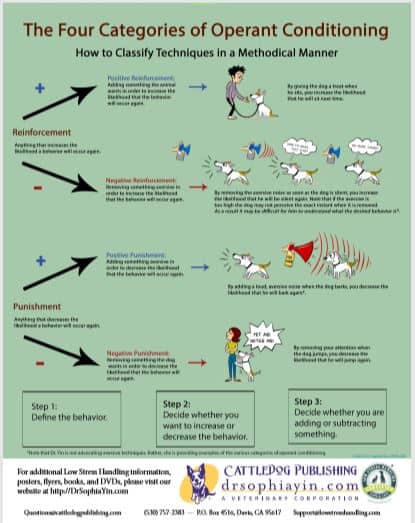

When you start a training program, you should become familiar with some basic training terminology. For starters, being able to identify the four different types of operant conditioning is helpful. The chart below is a simple description of the difference between reinforcement and punishment. And then within those categories, whether it is positive (adding something to the dog’s environment) or negative (withdrawing something from the dog’s environment).

There are a lot of different opinions regarding the best way to train dogs. However, most veterinary behaviorists agree that positive punishment should be avoided during training, as it can increase a dog’s fear and anxiety, which can then increase reactivity.

Alternatively, a dog could suppress the behavior being punished while still feeling anxious and escalating on the ladder of aggression. For example, if you train a dog not to growl. He may just skip growling next time and go right for the bite.

As mentioned above I recommend each reactive dog is evaluated by their own veterinarian. Some cases will then be referred to a veterinary behaviorist. Each dog requires a custom-tailored plan.

On this website, I will discuss my opinion and what works for my dog. But remember, just because I am a veterinarian, I am not YOUR dog’s veterinarian and each case is unique.

For those looking to get started with training and behavior modification for their reactive dog, here are a couple of resources.

- CARE for Reactive Dogs

- Dr. Sophia Yin

- Patricia McConnell

- Dr. Jen’s Dog Blog

- New Horizon’s Veterinary Behavior Services

- Click to Calm book by Emma Parsons

- Below is a link to this book on Amazon. As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

Key Points/Take-Aways

It is important to remember that reactive dogs are not bad dogs. Most of them are just fearful and anxious. And some are just over-aroused and excited. Either way, the key to successfully staying active with your reactive dog is two-fold, involving good management and implementation of a behavior modification training program.

Over the next year, stay tuned for blog posts covering all the topics you need to know to happily and successfully hike and otherwise stay active with your reactive dog. We will be discussing topics like the best gear for hiking with a reactive dog, teaching your dog to relax, teaching loose leash walking and focus on the trail, as well as sharing more of our story.

If you have a topic you would like to read a blog post about, please comment below and let us know.

Kate, I cannot tell you how much I’m looking forward to reading this series.

Lizzie is reactive. She started more with boundaries like fences, but worked her way to reacting to other dogs whenever she was on leash. I couldn’t participate in most of the exercises at our trainer’s weekly drop-in class because I would spend all of my time managing Lizzie with the direction & help of our trainer. While we might make small progress at class, I kept feeling like every time I was just walking with Lizzie, I would regress several steps.

Last fall, Matthew and I decided to spend the big bucks for a 4-week board-and-train with our trainer so Lizzie could have time to reset her habits. Our trainer has a strong bond with both our dogs, which we knew would help Lizzie understand the protocols. Plus she could practice them with someone who has precise training timing. Our trainer also offers other perks to BNT clients, so we knew it was money well spent. I’ve continued following the program our trainer laid out for us, and I’ve seen such improvement in how Lizzie interacts with the world, which makes me so happy.

We love being active too, so I’m familiar with many of the resources you list here because I was seeking information for months. But these topics are complex, so reading more perspective is always good. I am really looking forward to learning even more, and reading your story and how you’ve progressed with Glia.

Irene,

Thank you for commenting and sharing some of your own story with Lizzie.

I am always surprised by how big the reactive dog community is. I don’t know about you, but when Glia first started demonstrating reactive behaviors, I felt kind of alone in the struggle. Over the years, I have begun to realize that there are so many dogs out in the world that struggle with reactivity. And it is so nice to have others share their personal struggles and success stories. Lizzie is adorable and I am glad that she is able to interact more confidently and calmly with the world around her now. From what I have read on your blog/social media, you do a lot of training and enrichment with your pups. Lizzie is lucky to have you.

Regardless of whether or not I can offer any new perspective, thanks for your support! I look forward to seeing what you and Lizzie accomplish in the future. I love seeing reactive dogs live great lives.

I love your description: “Every dog reacts to stimuli around them every day. A reactive dog is simply a dog who “overreacts” to normal stimulus.”

While my dog isn’t “reactive” in the typical fear-reactive sense, he has a really strong prey drive and completely over-reacts with even the scent, much less the sight of deer, coyotes, and other critters. Many of the behavior modification techniques are the same, the main issue I have is inconsistent training opportunities, the wild critters just don’t cooperate!

Thanks! And I agree, it is really tough when training opportunities are inconsistent and slightly unpredictable. You never know when you are going to run into some deer. Glia always wants to chase squirrels and deer, but luckily she has improved in those areas as well as we have worked on her impulse control. I hope your pup continues to improve also despite the difficulty of not being able to set-up training opportunities as easily.

Same here, very strong pray drive in my now 9 year old Border colie Anja. Basically anything that moves trigers an overreaction (an attack) without any consideration of size, small critter or a bear. She chased a adult bear up a tree in our back yard. He was terrified. Does not seem to be fearful at all.

And I am not sure she distguishes between dogs and other animals when we meet them. She will lock on and try to go for it almost immediately. On the other hand she has lived safely at home for years with cats and kids. If I have time and control of the sitiuation she will habituate to specific animals slowly and never forget it, even after few years of absence. I have learned to manage her reactivity. I could probably habituate her to the few dogs that we meet on walks, but its very hard to get cooperation of other dog owners. We live in the country and its fairly easy to avoid other dogs on walks. Its not easy to own one of these dogs.

Thanks for posting this. I have one of both … Dog #1 is my perfect dog (ok, mostly perfect / she does find rabbits & skunks way too fascinating). She loves to say hello to other dogs when we’re out for a walk. Dog #2 is a Chihuahua mix … she’s good with dogs she’s familiar with (any size) and other dogs her size. With unfamiliar dogs – she does introductions about as well as a rabid raccoon. I’m hoping to work on that so we can have more pleasant interactions when we cross paths with other dogs.

Thank you so much for this! I have had a reactive dog for 6 years and it can be so overwhelming and lonely at times. It’s lovely to read something written from a point of view that I can relate to.